Stephen Rose for the NYTimes

New York Times Obit:

October 18, 2009

Donald Kaufman, Collector of Toy Cars, Dies at 79

By DENNIS HEVESI

It started in 1950 with a $4 purchase from a friend: an International Harvester Red Baby truck. It grew into one of the largest and most valuable collections of antique toy cars and trucks in the world.

Donald Kaufman, whose trove included a highly prized 1912 Märklin live-steam fire engine before he began auctioning off his treasures in March, died on Monday at his home in Pittsfield, Mass. He was 79.

The cause was a heart attack, his wife, Sally, said.

More than 7,000 cars and trucks were parked bumper to bumper on the plain white shelves that Mr. Kaufman had bought at Home Depot and assembled himself, wall to wall and floor to ceiling, in the four-level annex to his modest country home in western Massachusetts. There were also airplanes and a smattering of other vintage toys.

His “toys” were only distantly related to the products, mostly made of plastic, that Mr. Kaufman had helped to sell over the years as vice president of the KB Toys store chain, from which he retired in 1981. Some of the pieces he owned, like the Märklin steam engine, were detailed works of art that actually worked.

Mr. Kaufman owned vehicles of all kinds: taxicabs (small, medium and large), old trucks bearing signs for brands from long ago (Richfield Gasoline, Filene’s Sons, Sheffield Farms Sealect), ice trucks, water trucks, dump trucks and fire engines. Mostly, they were made of cast iron, tin and pressed steel. A white, windup “Gordon Bennett” race car, made around 1910 by Guntherman in Germany, had a small bellows connected to the rear axle on the underside, so that it could still emit a rumble nearly a century after it was made.

“He owned almost every known variation of every known automotive toy,” said Richard Bertoia of Bertoia Auctions in Vineland, N.J., which is handling the sale of the Kaufman fleet. “Among collectors, he has been clearly declared the most important force this hobby has ever seen.”

In June, three months after the first in what is to be a series of auctions, Mr. Kaufman guided a reporter for The New York Times through what he and his wife called “the museum,” pointing out, however, that only about two dozen other people had ever been inside.

Asked why he was letting go of his beloved toys, he simply said, “It’s time for me to sell.”

And sell they have. At the first session, in March, about 1,400 of the 7,000 toys brought in $4.2 million, well above the $3 million that had been estimated. A three-foot-long train of hand-painted clown cars drew the highest price, $103,500.

At the second session, in September, about 1,100 toys were auctioned, bringing in approximately $3 million. The 1912 Märklin fire engine — 18 inches long, with an exposed boiler and intricate gear work in an open frame — drew the highest price, $149,500. Three more sessions are planned, the first next April.

Starting with that International Harvester Red Baby truck (it has not been sold yet, but is likely to go for a few hundred dollars), Mr. Kaufman spent much of his time over the last 59 years combing through antique stores, bidding in countless auctions and cultivating relationships with toy dealers. He and his wife spent vacations searching the market in Europe and attending nearly every toy show in the Northeast.

“These aren’t my toys,” Mr. Kaufman said in June. “I am just taking care of them.”

Donald Lewis Kaufman was born in Pittsfield on Oct. 8, 1930, one of three children of Harry and Ruth Klein Kaufman. In 1922, his father and uncle started a wholesale company, Kaufman Brothers, that distributed a variety of goods, including candy, soda, stuffed animals, watches and razors.

After attending North Adams State College in Massachusetts and serving in the Army in the early 1950s, Donald Kaufman joined the family business. In 1958, Kaufman Brothers expanded into retail. It became KB Toys in the 1960s and became entirely a retailing operation in 1972. As vice president, Mr. Kaufman played a role in expanding the chain to malls in almost every state. KB was sold to the Melville Corporation in 1981 and went out of business in 2008.

Mr. Kaufman’s first marriage, to the former Faith Dichter, ended in divorce. Besides his second wife, the former Sally Golden, he is survived by his sister, Joan Poultridge; three daughters from his first marriage, Suzanne Ascioti, Deborah Mager and Judith Wortzel; and four grandchildren from his first marriage. He is also survived by a stepson, Jack Roche; a stepdaughter, Mary Ellen Simon; and five step-grandchildren.

A deep fascination impelled Mr. Kaufman’s collecting.

“He didn’t just see a toy,” his wife said. “He would look at that toy and think about the history. He thought about what it was made of, the design, the people who sat there and made it. He would hold it and say, ‘If only it could talk.’ ”

Earlier this Year on Homer.

From the New York Times, yesterday, comes news of more toys!!

After a Life Selling Toys, It’s Time to Sell His Own

By RICHARD S. CHANG

Pittsfield, Mass.

WHEN Donald Kaufman decided that he wanted to sell his personal toy collection, an unparalleled trove of some 7,000 antiques from around the world, the news spread quickly among collectors. And it provoked the sort of market upheaval one might expect if the Getty Trust announced it was getting out of the art business.

“Nobody knew just how many toys he had,” said Jeanne Bertoia, the owner of Bertoia Auctions of Vineland, N.J., which is handling the sale. “People saw what he was buying, but no one had seen his collection.”

Part of the allure comes from Mr. Kaufman’s role as a co-founder of the defunct KB Toys store chain, from which he retired in 1981. He has given no reason for selling the collection he spent 59 years amassing, except for a nod toward destiny. “It’s time for me to sell,” he said.

In mid-March, Bertoia Auctions sold a portion of the collection, more than 1,400 toys, bringing in $4.2 million, well above the $3 million that Bertoia had estimated. (Mr. Kaufman’s estimate was $2 million.) Another auction is scheduled for September, after which Mr. Kaufman will still own more toys than he’ll have sold. Four to five more auctions are planned.

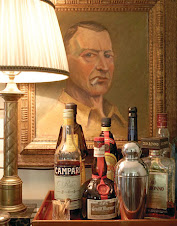

At 78, Mr. Kaufman is a tall man with a gentle grandfatherly manner that does little to reveal his ruthlessness in pursuit of pre-World War II toys. His approach to collecting combines erudition and gamesmanship. He enjoys telling the story of a particularly important sale. He rented a U-Haul trailer, hitched it to his capacious Ford Econoline van and parked the rig in front of the auction house as an act of intimidation against other potential buyers.

Transportation toys are Mr. Kaufman’s primary interest, and most pieces in the collection are cars and trucks. Airplanes are a distant third. The toys’ domain is a four-level windowless annex to the average-size country house here in western Massachusetts where Mr. Kaufman and his wife, Sally, live.

The Kaufmans call it “the museum,” though that makes it sound extravagant or grandiose, which undresses some of its charm. Mr. Kaufman assembled the displays himself. He bought plain white shelves at Home Depot and installed them himself. Entering the Kaufman museum, a visitor found antique toy cars parked bumper to bumper on shelves that ran wall to wall and floor to ceiling. There were taxicabs in small, medium and large. Old trucks bore signs for brands long gone: Richfield Gasoline, Filene’s Sons and Sheffield Farms Sealect. There were ice trucks, water trucks, dump trucks and fire engines. The floor — covered with carpet the color of blue topaz — was occupied by a small fleet of pedal cars.

“There are no duplicates,” Mr. Kaufman said proudly in a voice graveled by age. “Only variations.”

Some of the variations were so slight that it was difficult to see the differences. Along one stretch of wall, two red tow trucks were berthed nose-to-tail, one with round windows and the other with square ones. A line of four cast-iron taxicabs from the early 1920s provided an excellent exercise in observation — the only variations were in the color of the tires (silver and white) and hoods (orange and black). The March auction did little to decrease the jam in the museum, so there was not much room to move around.

Ms. Bertoia said the collection was divided into five categories: pedal cars; American cast-iron toys; tin toys, which are more delicate and mostly from Europe; pressed-steel toys; and light pressed-steel toys, including those from an American toymaker, Kingsbury.

“Usually you’d see between 25 and 30 toys in a good collection,” said Mike Bertoia, Ms. Bertoia’s son, of the Kingsburys. Mr. Kaufman, he said, has more than 150.

It takes a moment to see anything other than the sheer magnitude of the collection. Tighten the focus and intricate details emerge: the mechanical meter in a taxi, a hand-painted mustache on a driver, the brass fixtures of a fire engine’s water pump. The auction catalog showed that most were in very good, excellent, near-mint or pristine condition.

Sitting on a shelf along the staircase between the first and second floors, a white wind-up “Gordon Bennett” racecar made around 1910 by Guntherman of Germany hardly looked a century old. On the underside of the car was a small bellows connected to the rear axle, which Mr. Bertoia said still provided the car with engine noise. Another German toy, the Märklin Fidelitas, a whimsical three-foot-long train of delicate hand-painted clown cars, brought $103,500, the highest sale price at the first auction.

Mr. Kaufman likes to say that he wonders what the toys would say if they could talk. He explained that when he looked at an Arcade Mack high dump truck, he saw more than a toy vehicle. “I see the rubber factory that made the tires,” he said. “I see the metal factory, the press — the original cars.”

Born and raised in Pittsfield, Mr. Kaufman was always interested in antique cars and trucks. The first toy in his collection was an International Harvester Red Baby truck that he bought for $4 in 1950, the year he began working for the family business.

KB stands for Kaufman Brothers. Mr. Kaufman’s father and uncle founded the company in 1922 as a wholesaler. They carried goods as diverse as confections and sundries, sodas, razors, stuffed animals and watches, Mr. Kaufman said. Toys did not come along until after World War II.

In 1958, Kaufman Brothers expanded into retail, became KB Toys in the 1960s, and stopped wholesaling altogether in 1972. Mr. Kaufman does not boast about his role in the business, but he was the first vice president and had a hand in turning KB Toys into one of the biggest toy chains in the world, with hundreds of stores across the country.

Mr. Kaufman attended his first major auction shortly after he retired and found a community that welcomed his growing curiosity about antique toys. “I started talking to other collectors,” he said. “You learn everything from them.”

Mrs. Kaufman was not with her husband for that first auction — they met in 1988 — but she has been involved in his hobby since they have been together. A smartly dressed woman with short red hair who could draw comparisons to the actress Leslie Caron, she drove the van to many of the auctions and set up the vendor displays at toy shows for pieces that Mr. Kaufman wanted to sell.

Mrs. Kaufman told a story about one of her first experiences, when the collection of the closed Perelman Toy Museum in Philadelphia was being sold. The sale was held in the museum, and the buyers — each guaranteeing to spend at least $50,000 — had to race for the pieces they wanted.

She smiled and her eyes shone brightly as she told the story. And in many ways, the Kaufman collection is a diary of their lives together. The annex is a very private place. Mr. Kaufman said fewer than 25 people had been inside.

But if he is sad to see the collection go, he is not showing it.

He said he was not keeping a single toy, not even that first International Harvester Red Baby truck. “These aren’t my toys,” he said a couple of times during the day. “I am just taking care of them for now.”

But there are clues everywhere that the toys are more than just a passing interest. On the staircase between the first and second floors, Mrs. Kaufman pointed out a step ladder and two wooden planks.

“Don put those planks on top of the ladder and stood on them when he arranged the shelves above the stairs,” she said. She considered that thought for a moment, shook her head, smiling, and disappeared upstairs.

Emily Eerdsmans does Palm Beach: Kips Bay that is!

-

Beloved Author, historian, shop keeper, and DESIGNER Emily Eerdmans has

participated in this year's Palm Beach Kips Bay Decorator Showhouse! The

results ...

1 week ago

No comments:

Post a Comment